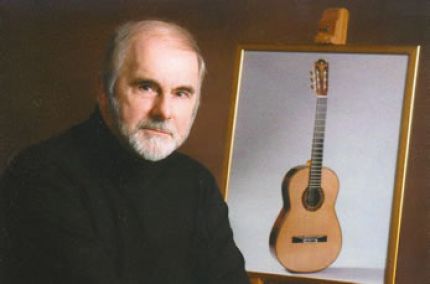

Biography

Born on the Isle of Man but brought up in the city of Oxford, it was here that he began his career under the tutelage of the renowned harpsichord maker Robert Goble, making instruments within the finest European tradition. Further study at the Oxford College of Art and Technology completed his training.

Paul is rare in having this skill with different instruments but his love of the guitar led him to a chance meeting with the late David Rubio, at Duns Tew, Oxfordshire, a renowned place visited by Julian Bream and John Williams. As chief instrument maker and manager he remained with Rubio for a number of years. Success with his own instruments during this period under the Rubio label and stamped P.F (which can still be seen in use today), led him to establish his own studio in 1975.

In 1983 he was awarded a Winston Churchill Travelling Fellowship to extend his research into the forest of Brazil. Paul Fischer has served as an advisor to the crafts Panel for the Southern Arts Association, and also as a Technical Advisor and Panel Member of the Crafts Council of Great Britain. He still dedicates his life to making fine instruments with a panoramic view of the Cotswold Hills from his workbench.

As the classical guitar has joined the mainstream in the second half of the 20th century, he has been one of the figures in the vanguard and at the cutting edge of the evolution of the modern concert guitar. His instruments have been featured in many publications including the best seller The Complete Guitarist by Richard Chapman (Dorling Kindersley 1993), and The Classical Guitar: A Complete History by John Morrish et al (Balafon 1997).

Paul Fischer Interview by Woodley White

After fifty years of instrument making, Paul Fischer is still innovating…

…exploring, and refining his craft. An artist who began in the world of reproduction, Paul has had the opportunity to study and work with seminal thinkers in the world of lutherie. He has also explored alternative woods for guitar construction. With his British accent, good looks, and witty spirit, he reminds me a little of James Bond — I mean Sean Connery. He’s bright, personable, and insightful. I caught up with him at the Guitar Foundation of America convention in Columbus, Georgia in October 2006.

Paul, it’s really a pleasure to interview you. I’ve heard a little about your hometown having a celebration for your fiftieth year of instrument making. That must have been quite an honor and a fantastic event. But let’s go back and start at the beginning.

‘In my last term at school, the music master asked if there was any pupil interested in making musical instruments. My school was in Oxford and the master was a friend of the world-renowned harpsichord maker, Robert Goble, also living and working in Oxford’

‘Goble and his son Andrea were very fine craftsmen, the former having worked and studied with Arnold Dolmetsch before the war. It was therefore extremely fortunate that I was offered this unique opportunity to work under such highly respected instrument makers.

This opportunity so fascinated me so I decided to take it. Normally one would go on to college and then to the university, but instead I received five years training with Robert Goble as an apprentice. He was strict, very thorough, and very talented and skilled. I feel I was very fortunate. This was in 1956, and there being no formal training in this unusual profession, it was rare indeed. This was a chance not to be missed. There was no training other than training with an established maker back then.

What happened after your apprenticeship?

I went on to college for two years and then entered military service for four years. I was a tank commander in Northern Germany. Another stroke of luck came when I got out of the army and discovered that there was an instrument maker in North Oxfordshire who wanted someone to make guitars with him. The idea of making instruments other than harpsichords was very interesting. I went to see him very early one morning and he was still in his pajamas. This was David Rubio. I said to him, “I understand you are looking for someone to make musical instruments.” He asked, “What can you do?” So I responded, “I’m a harpsichord maker.” David said, “I make guitars and lutes, but I’ve always wanted to make harpsichords. When can you start?”

David Rubio had been in Oxford for six months…

…Previously he had been at Julian Bream’s estate where he lived and worked in a converted barn. I joined him two weeks later to learn how to make guitars and lutes, and I taught him about harpsichords. It was very much a collegial and reciprocal relationship. I began making instruments about six years before David started, but he had set out on his own as a luthier where I hadn’t. I was still looking for a broader experience.

David Rubio’s importance in teaching and his ideas about making guitars in particular had an influence on English guitar making, which hardly existed before. But this was February 1969 and he wanted to broaden his work into other instruments, and the first thing he did was get involved in harpsichord making. From then on, I made nearly all the guitars. They carried the Rubio label but “PF” was stamped inside the instruments I made. Because of my formal training, I produced a lot more instruments than Rubio. Many of the guitars made between ‘69 and ‘75 carry my initials.

In addition to harpsichords, David began to take an interest in the viola de gamba, Baroque cellos, and Baroque violins. Within a year we had so many commissions (about a four- to six-year waiting list) that we increased the workforce to eight. I took over as manager and daily administrator.

What do you consider the major contributions of David Rubio to the world of guitar-making?

I would say his ability to market and sell his work, his ideas, and his passion. Considering he was self-taught, his ability then to form a new idea and explore that idea in the instruments was quite phenomenal. Because of his connection with Julian Bream, he created an instrument that was clearly different from the Spanish school of making.

Before Rubio we had a few important indigenous guitar makers in England…

…He brought his approach, his experience working for Julian Bream, and that controlled and influenced the quality of the instruments he was creating, which in turn established the English school of guitar making. Due to Julian Bream we had leading players coming from all over the world to buy instruments.

It was very important because many of the new English makers were influenced to make and to develop their own careers — people like me, Kazuo Sato, Brian Cohen, and later Simon Ambridge, Michael Gee, and Kevin Aram. His influence stretched to makers in other countries It was the power of his make-up. It was a fascinating period because up to this time most players would simply go to Spain to buy a guitar apart from the Hauser instruments.

Rubio had an innate understanding of the materials with which he was working. He knew how to explore their properties and get the best out of the material, which even to me, as a formally trained maker, was a completely fresh approach to making musical instruments. His analytical examination of the material and its characteristics, to see how to get it to work at its best, was perhaps one of the most important lessons I was learning as a maker.

I would say a lot of his ideas were formed around the traditional ways of building at that time. In fact, a few years later, when a physicist approached him about cooperation in his research, Rubio almost rejected it out of hand. He didn’t like the idea of a scientific approach. The physicist then came to see me because I was renting space in David’s workshop. I wanted to see if what the physicist was doing could be of value. It was because of that meeting with Dr. Bernard Richardson that I later went on to develop the “taut” system of guitar making.

I greatly admired and respected David. He was very important in my life. He encouraged me to take a look at making in a different way. Instead of looking at a set of plans or simply copying, he demonstrated how important it is to work out things for yourself. He taught me how one should analyze and challenge oneself in order to gain an understanding of the fundamentals.

Tell me about your life after your collaboration with David Rubio….

In 1975, I left and set up my own studio, also in the county of Oxfordshire… Shakespeare country. From then on I was totally independent in thought, word, and deed. Taking what I learned from Bernard Richardson, I began to develop instruments that were mine and not clones of Rubio.

At the beginning of the 1980s, I was awarded a Winston Churchill Research fellowship. This was mainly to do research in Brazil on the supply of Brazilian rosewood, its future availability, and alternatives to rosewood from that region. I was to spend time in Sao Paulo in research institutions forestry management and maintenance and study of different species — doing the groundwork for a trip into Bahia, Pará, EspIrito Santo, and Pernambuco. So I flew from the study in Sao Paulo to Belem where I attended an international conference on the sustainability of the rainforest and the best use and management of rainforest materials and species.

While I was in Belem, I went into the rainforest of that region to get a better understanding of how they were being managed and visited timber merchants and lumber mills to broaden the picture of the general state of the timber industry, conversion, and export. I then flew down to the state of Bahia to meet up with a Hungarian timber merchant who specialized in lumber for instrument making and I spent two weeks with him meeting and gathering information about the availability of Brazilian rosewood, what future supplies may or may not be, and gathering samples of alternative woods.

What did you find?

Things were bleak. Many of the timber mills had thousands of logs lying around but the mill was no longer working. They laughed when I asked about Brazilian Rosewood. They didn’t understand I was doing research. They thought I was trying to buy it. From a timber merchant’s point of view, it was uneconomic to try to gather a few logs of Brazilian rosewood. Commercially, it wasn’t worth the merchant’s looking for From Central Bahia, I traveled by bus down through Pernambuco, to São Paulo, stopping in various regions. The future supply appeared desperate.

By the time I had returned to São Paulo and had to conclude that the future of Brazilian rosewood was extremely bleak and whether Indian rosewood would be the logical alternative, or whether makers would consider other woods, including some of the woods I brought back and used to make experimental instruments. The woods I had chosen were similar in color, density, and weight to Brazilian. This was a logical thing to do although I have since decided that there are many other kinds of wood that don’t look like rosewood at all but can work equally as well.

I chose seven other woods that I made into experimental instruments…

…identical in every respect to my normal work. Using one Brazilian rosewood guitar as the reference point, I held a presentation in London where these instruments were played and the audience was asked to judge the results in a blind test. No one could pick out the Brazilian instrument from the others. However, the general response of the audience was skepticism, partly because they assumed wrongly that I was trying to catch them out and expose their ignorance. That was not the purpose at all. It was a serious endeavor to deal with a looming problem, and at the same time gain valuable experience for myself as a guitar maker.

You have lived through a period where Indian and Brazilian were equal in value to where Brazilian prices had gone through the roof

Yes.

How did it go, selling these instruments made of alternative woods?

I did sell them all, but I sold them as experimental instruments below my normal price. I believe some of the skepticism toward alternative woods was born out of the natural conservatism of classical musicians. This seems strange in a world of art — where you would think that they would be much more curious about exploring different ideas.

By 1992, Brazilian Rosewood became banned, Appendix One of CITES. So that the work was well ahead of the game. I have to say it didn’t help a lot because of the conservatism of players. They still wanted Brazilian if we could get it as makers. In a sense that work coincided with the changes, I was making with my instruments due to the work with the physicist. It gave me a better understanding of the natural stiffness of the different components of the body of the guitar.

So you changed your approach to bracing at this time?

Yes, I did. It all happened together. I changed the bracing of the top, and I even experimented with the back bracing as well.

Using the ideas of Bernard Richardson, I decided to go to the drawing board with a clean sheet of paper and start afresh at working out a bracing system without referring to the traditional bracing system. This involved considering particularly the soundboard and the back of the guitar as stiff membranes which were supported in a way that was light but strong. Hence the grid system which of course now comes in many forms. The principle is the same — high stiffness, low mass.

I didn’t know anything about Smallman. This was back in 1977 before Smallman was on to that system. We developed independently and at different times. My inspiration was the physicist who encouraged me to develop my own work and given my background working with two very different makers.

In a way this evolution of guitar making in the last twenty years of the 20th century…

…when all these makers got together and had the courage to explore these new ideas, was the most dramatic period of change since Torres. By doing this exploring, we have learned so much more about musical instrument making that was never there before. The renaissance has been fueled by the sharing of information.

My background was in early music. Early music instrument making was all about copying. You can copy all you want without really understanding how things work. So it’s better to explore for yourself and in the process learn. I always think that people who use the word “tradition” to describe what they are doing represents a very blinkered approach that perhaps demonstrates a lack of confidence.

To be curious is a very healthy thing. Ask questions. Guitar makers should be the same way. A young student will plunge in and do some very strange bracing and will be learning. You will learn from your mistakes as much as from your successes.

Torres was a very important pioneer, but let us not deny that there will be a period where we can be making similar groundbreaking advances and for very similar reasons.

I see instrument makers and I’m careful to describe them this way, as artists and craftsmen — so I expect they will explore their ideas and push the artistic envelope. To be rigid about tradition is to stagnate rather than to push the boundaries. Growing is an important word in the world of instrument making.

Talking about artistic evolution and change, what directions are you going in now?

I’m continuing and steadily evolving the work I am already doing…

…changing in a controlled but productive way. Based on customer’s responses, I make changes. I hadn’t really made any to the taut system which I developed in the ‘80s until about four or five years ago. Because I feel very comfortable with the basic principle of that design, I’ve simply refined it, making small adjustments that have made dramatic impact. For example, I’ve changed the angle of the lateral braces. I’ve also changed from Euro spruce braces to Sitka spruce because Sitka is by nature much stronger, therefore I could reduce the dimensions of the bracing, reducing mass and weight, but maintaining the stiffness.

Did you hear a difference in sound?

The main difference is the feedback which the player receives. If you take the idea of the grid system to its logical conclusion, you continue the process of projecting the energy away from both instrument and player. The feedback I was getting from players was that they couldn’t really hear what the guitar is doing. By making these refinements, the player now can hear precisely what they want from the instrument without any loss of projection.

Please tell me about your fiftieth year celebration.

It is not fifty years as a maker because I did military service so interrupting my career, but the fiftieth anniversary of the date my career started. For this fiftieth year I was invited to give numerous lectures and the main celebration was on the third of September, coinciding with the actual date I began as a maker. This was held at the theater in my own town which also has an art gallery attached. This proved ideal for the event I wished to create.

Congratulations. Fifty years. That seems amazing. Can you tell me more?

I gave a forty-five-minute talk about the major influences in my life who were the early music instrument maker Arnold Dometsch and the late David Rubio. I also spoke on behalf of all instrument makers who I believe do not get the recognition they deserve as creative, talented, gifted, highly skilled artist craftsmen. I had recently been told that a musical instrument is only a tool.

That must have touched a nerve!…

To support my argument I referred to the great Dutch artists of the 17th and 18th centuries, whose work clearly demonstrated the respect they held for these elegant beautiful objects. This was followed by guest recitalists playing a variety of instruments I had made through the years from a copy of a Stradivari guitar, a vihuela, a 19th-century guitar, an 8-string in the Simplicio style, as well as numerous 6-string guitars. This was followed by the guests being invited to sample the food and the wine and view the exhibition in the gallery which included many examples of my work from harpsichords, spinets, lutes, and a whole range of guitars as well as many photographs from the Rubio workshop.

That sounds like a fantastic and well-deserved celebration. I want to congratulate you and say that you are an inspiration. I appreciate your grounding in the tradition as well as your openness to develop, expand, and experiment. With fifty years under your belt, in some ways you are the grandfather of modern lutherie, but with your creative approach you seem young at heart. I hope you have many more years to learn, to develop, and to share your perspective with the rest of us in the field.

Against The Grain

The immense success Paul Fischer has achieved in a remarkable career is, of course, not only due to his amazing gifts but also sheer hard work, his energy, combined with a passionate belief in what he wanted to create. Therefore, with this fascinating publication, we celebrate his artistic contribution and his supreme talent.

John Mills

Available from:

Presto Music. Books.

23-25 Regent Grove. Leamington Spa. Warwickshire.CV324NN. U.K

email: info@prestomusic.com

Buy from Amazon

Paul Fischer

Luthier & Author

List of Players -

Past & Present

-

Pepe Martínez

Assad Brothers

Marcelo Kayath

Ruben Riera

Jukka Savioki

Amsterdam Guitar Trio

Eduardo Fernández

Badi Assad

John Mills

-

Jason Vieaux

Abreu Brothers

Gerald Garcia

Hill Wiltschinsky Duo

Paulo Bellinati

John Taylor

Omega Guitar Quartet

Forbes Henderson

Jason Waldron

Pavel Steidl

Juan Martin

Xuefei Yang